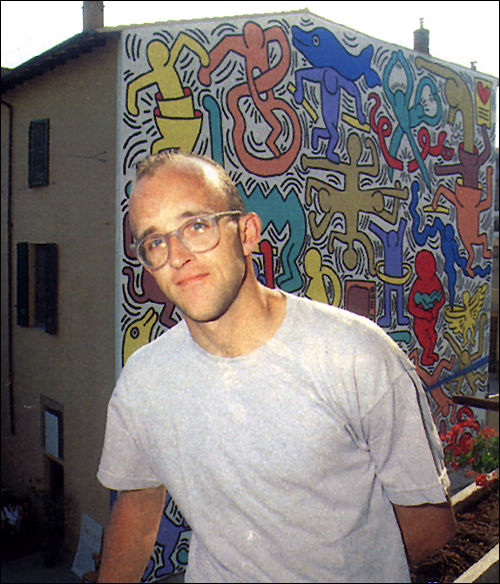

In April 1986, Keith opened the Pop Shop, a retail store in New York. He explains his philosophy in selling his art through a commercial venue:

“My work was starting to become more expensive and more popular within the art market. Those prices meant that only people who could afford big art prices could have access to the work. The Pop Shop makes it accessible.”[14. Sheff, p. 64]

Before, during and after the opening of the Pop Shop, Keith was dogged by a critical ambivalence towards his work, stemming from its broad popularity.

“It’s frightening how much power critics and curators have. People like that have enough power to write you out of history…”[15. Sheff, p. 66]

“…I think that in a way some [critics] are insulted because I didn’t need them. Even [with] the subway drawings I didn’t go through any of the ‘proper channels’ and succeeded in going directly to the public and finding my own audience…I bypassed them and found my public without them. They didn’t have the chance to take credit for what I did. They think that they have the role of finding the artist…and then teaching the public….I sort of stepped on some toes…”[16. Rubell, p. 59]

Keith ultimately found acceptance where it counted most for him.

“The things that have always given me the strength and confidence not to worry about [negative criticism] are, first of all, support from other artists, artists whom I look up to and respect much more than I respect these critics or curators, and second, things that come from real people, people who don’t have any art background, who aren’t part of the elitist establishment or of the intellectual community but who respond with complete honesty from deep down inside their hearts or their souls.”[17. Sheff, p. 66]

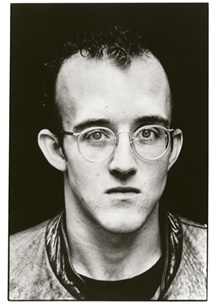

In 1988, Keith was diagnosed with AIDS. By that time, AIDS had already deprived New York City, the art world, the world at large and Keith himself of many friends and luminaries. The diagnosis did not come as a surprise to Keith. He publicly acknowledged his illness in a remarkably candid interview in Rolling Stone magazine. Keith’s response to his illness was characteristically philosophical.

In 1988, Keith was diagnosed with AIDS. By that time, AIDS had already deprived New York City, the art world, the world at large and Keith himself of many friends and luminaries. The diagnosis did not come as a surprise to Keith. He publicly acknowledged his illness in a remarkably candid interview in Rolling Stone magazine. Keith’s response to his illness was characteristically philosophical.

“No matter how long you work, it’s always going to end sometime. And there’s always going to be things left undone. And it wouldn’t matter if you lived until you were seventy-five. There would still be new ideas. There would still be things that you wished you would have accomplished. You could work for several lifetimes….Part of the reason that I’m not having trouble facing the reality of death is that it’s not a limitation, in a way. It could have happened any time, and it is going to happen sometime. If you live your life according to that, death is irrelevant. Everything I’m doing right now is exactly what I want to do.”[18. Sheff, p. 102]

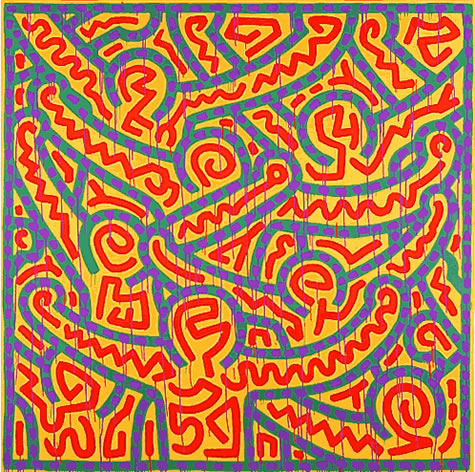

“All of the things that you make are a kind of quest for immortality. Because you’re making these things that you know have a different kind of life. They don’t depend on breathing, so they’ll last longer than any of us will. Which is sort of an interesting idea, that it’s sort of extending your life to some degree.”[19. Daniel Drenger, “Art and Life: An Interview with Keith Haring,” Columbia Art Review, Spring 1988, p. 49.]

Of course, Keith’s reputation has continued to grow, and his work is more widely admired now than ever before. Keith had broader concerns, however, than extending his reputation as an artist. Before his death, he established the Keith Haring Foundation to continue his charitable support of children’s and AIDS-related organizations.

Keith’s contribution to the art of the 20th century is difficult to fully appreciate, because ultimately he transformed our idea of what art is. When once asked to state the values he was trying to impart in his work, Keith replied,

“A more holistic and basic idea of wanting to incorporate [art] into every part of life, less as an egotistical exercise and more natural somehow. I don’t know how to exactly explain it. Taking it off the pedestal. I’m giving it back to the people, I guess.”[20. Drenger, p. 53]

FOOT NOTES