In the 1960s and the 1970s, the New York subway system, and the city’s doorways and blank walls, became internationally famous as the breeding ground and blackboard for the most fertile and pervasive crop of graffiti artists since “Kilroy was here” in the aftermath of World War ll. It is, perhaps, no accident that in both instances stress and danger – combat conditions and a certain camaraderie – prevailed.

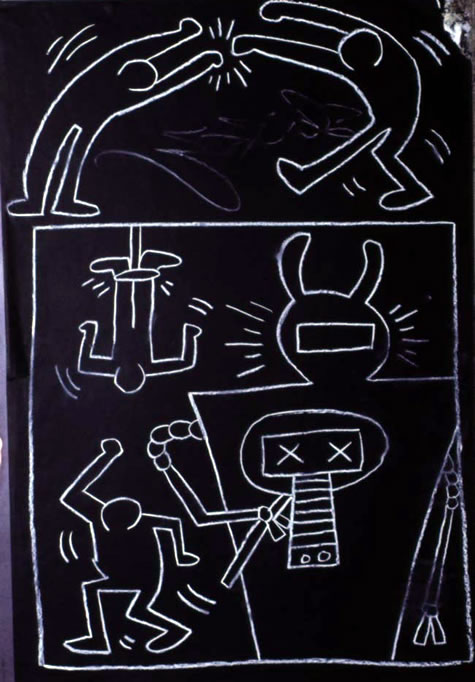

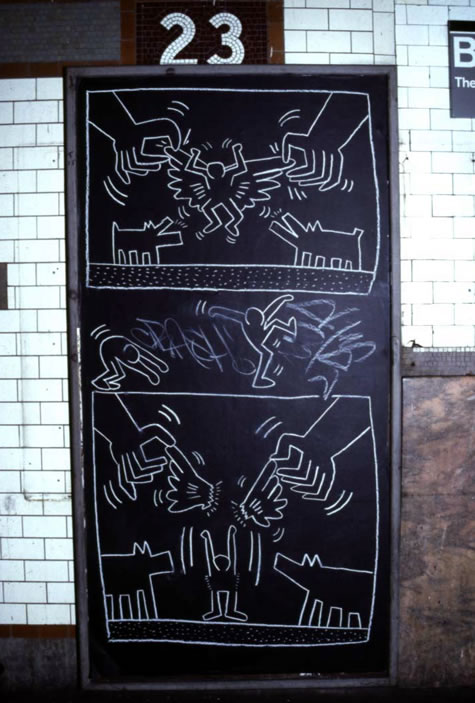

Untitled, 1984, Chalk on paper | 88 1/2 x 46 inches

Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

The graffiti artist, or “writers” as the prefer to be called, graduate at any age between eleven and sixteen , from the schools and sidewalks to that olympic arena – public transportation. Enormous media attention has been focused on them. There has been, however,no unanimity of opinion on their value or on what their presence indicates about our society. What to one observer seems a healthy artistic outlet for rage, frustration, and the opportunity to identity in a culture which only “stars” are admired, is to another the unsightly defacement of public property – a Bronx cheer at government and authority.

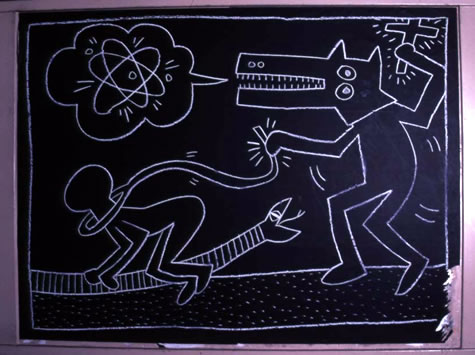

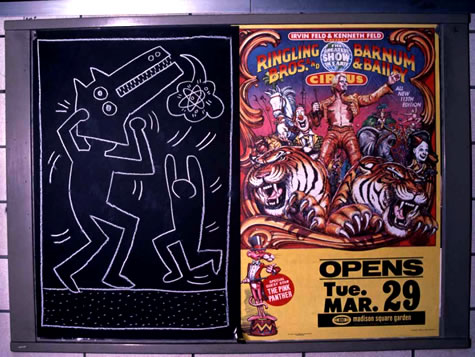

Untitled, 1984 | Chalk on paper

Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

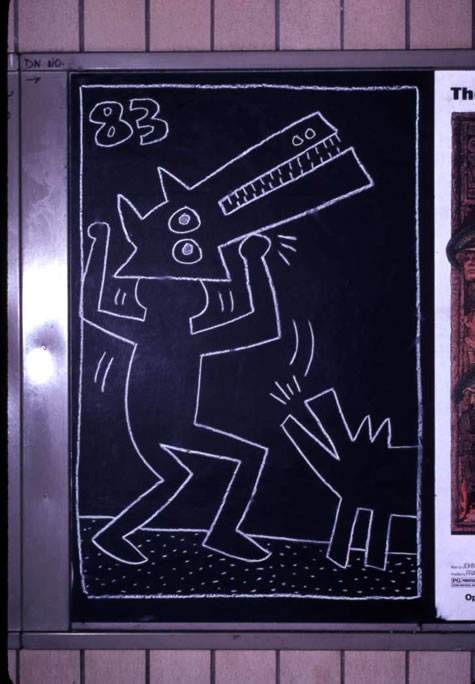

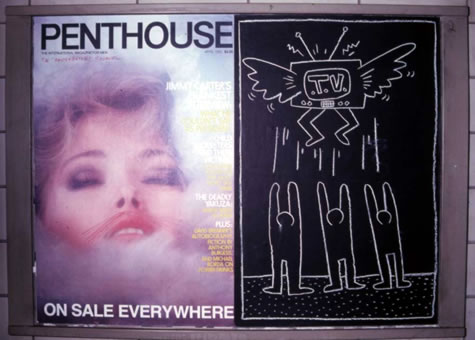

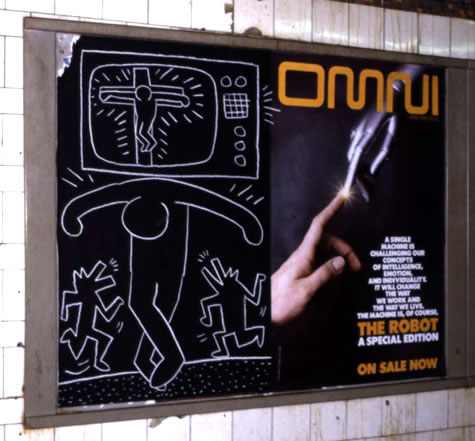

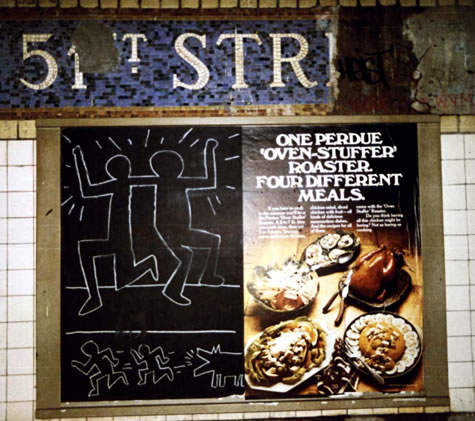

Since the 1980’s, a new presence has been seen and felt in New York City’s street and subways. Radiant Babies, Barking Dogs and Zapping Spacecraft, drawing simply and with great authority, have entered the minds and memories of thousands of New yorkers. Our instant familiarity with this new pantheon of characters coincides with our rapid recognition that a sympathetic sensibility is at work in our midst. This call to attention, stronger than that exerted by the colossal glut of advertising or official signage, sets the work of Keith Haring apart from other graffiti writers. The man responsible for all this cheer never signs his work Keith Haring’s gift to the public is generous and heartfelt – a celebration of the spirit that is not and cannot be measured in dollars.

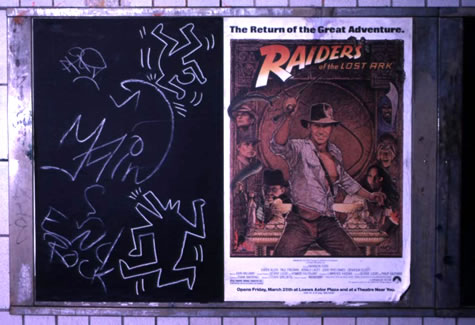

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

In the past to years, a parallel set of images has also been appearing in art galleries and museums. Fed by the same genius for the apt image and its inspired communication, Keith Haring’s painting in black and white and, occasionally in Day-Glo green, oranges, and purples, have had immediate and international success when exhibited as fine art. It is this parallel career as a professional artist that has allowed Haring to continue his work in the streets and subways. Haring forces the fine art collectors of his work to subsidize the more public and unremunerated aspect of his activity. While this doesn’t cause Haring the slightest confusion (he is perfectly able to harbor more than one idea at a time), the oversimplifiers wonder aloud: Does Keith Haring work for all New Yorkers or has he been coopted by the System, by exhibiting in commercial galleries and museums? The truth here, as so often, is not either/or; it is both and at once.

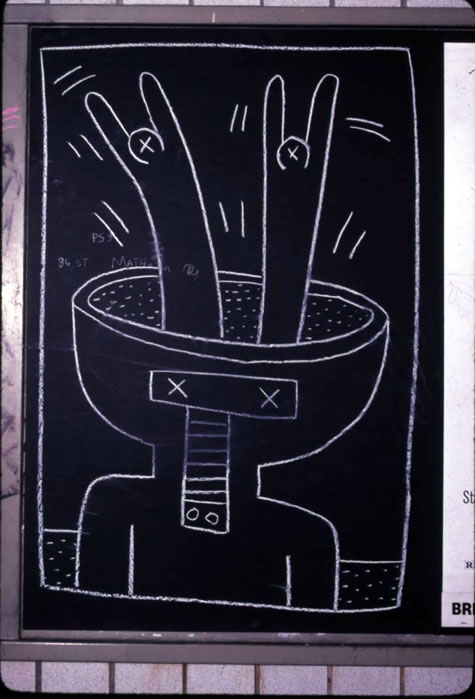

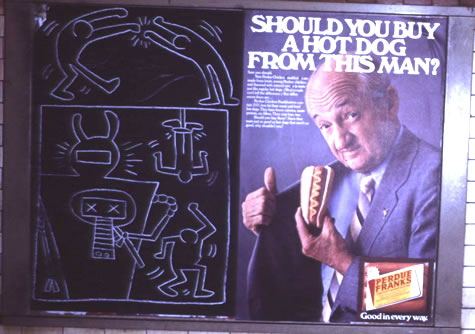

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Keith Haring’s work appeals to us on several levels. First, of course, is the goofy cheerfulness that strikes immediately and, through repetition, becomes a leitmotif that sees us through our days – a tuneful celebration of urban commonality. When we spot the Radiant Baby or Barking Dog, we not only have seen them before and know we will see them again, soon we also know that tens of thousands of our fellows will see them as well.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

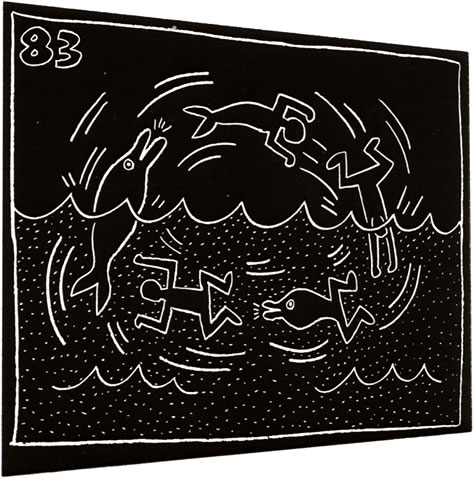

Keith Haring has developed his own language, which speaks to us with immediacy in a deeply preverbal sense. Each term in this language can be read as subject, verb, or object: the Dog Barks the Spacecraft or the Spacecraft Zaps the Praying Man. In much the same way as Chinese or Egyptian languages are written pictographically, Keith Haring’s world is made up of symbols that speak urgently to us, both alone and in interchangeable configurations. And as the pictographs or hieroglyphs communicate visually, soundlessly, so too are Haring’s symbols swathed in silence. An eerie quietude surrounds all his work, heightening and animating the dramas they depict.

Untitled, 1983 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Behind an apparent ease of invention in Haring’s work lies much visual knowledge and sophistication. As a child Keith Haring’s ambitions was to be a cartoonist and illustrator. His ease, fluency, and comic invention were astonishing at an early age. He enrolled in commercial art school in Pittsburgh bu t left after six months with a newfound dedication to the fine arts. It was in Pittsburgh, living on his own, that he happened o the Pierre Alechinsky exhibition at Carnegie Institute in 1977. Alechinsky in 1977 was a curious choice as the subject of a retrospective; his graphic style, which evolved in the 1950’s could not have seemed more out of phase in the minimal preponderance of the late 1970s. In the elegantly agitated graphism of Alechinsky, Haring saw that expressionism (abstract and European at that) was again an option – an energetic prototype that could be absorbed and proffered again.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Haring hit upon the connections between his urgent cartoons and Alechinsky’s equally agitated although less specific message. but he soon realized that to evolve from the abstract draftmanship that was engendered by this contact, a wider field of influence and stimulus was needed. It was specifically to enroll in the School of Visual Arts that Haring came to New York City in 1978. A quick study, he soon absorbed and moved beyond the information, styles and available attitudes at that curious institution, which is at once naive and hip. Ultimately, Haring’s transition to the stunning new vocabulary of Pulsing Pyramids, Praying Figures and Hovering Angels was the result of a few months in New York City, driven by the hunger to communicate to a popular audience – one that lay outside the official art world.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

What presuppositions lie behind Keith haring’s work? What exactly is his attitude toward his subject matter. Clearly, much sexual energy is abroad in his work, – sexual energy being so powerful a part of our natures that in the healthy world Haring projects there is nothing to hide; indeed, exuberance abounds. Haring is acutely aware of this message in his work and keeps any specifically sexual images in the studio and out of the eye of the general public. “Kids like the drawings and I don’t want to endanger that.”

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

The terror and horror at the use of nuclear power and ever -present fear that through accident or intention an “incident” might occur are omnipresent in Keith haring’s drawings. (His hometown of Kutztown, Pennsylvania, is only fifty miles from Three Mile Island.) The Spacecraft Zaps a Pyramid, endowing it with radiant power; Running Men brandish pulsing bars of energy. Power is unleashed and manifests itself at all times and in every confrontation. Exchanges of energy from person to person and from “inanimate” objects to individuals are one of the key transactions in all of Keith Haring’s work.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Haring’s sense of drama, of incident, is always strong and clear. Drawn in chalk on the black paper panels that the Metropolitan Transit Authority uses between rentals of advertising space, and in black sumi ink or Magic Marker on paper, oak tag, fiber glass, or vinyl tarpaulin, Haring’s designs and prodigious inventiveness are always in the service of immediate unmediated communication. The drama is so heightened that we often get the sense that the scene before us is a “still” from an action that has a past and a future. The toil involved in working up these scenes of great apparent spontaneity always takes place in the privacy of the studio.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Whether we are faced with a religious ceremony, a science fiction vignette, a love-dance, or a confrontation of antagonists, there is in all Keith Haring’s work an intensified recognition of the drama of modern life; we can all identify with the Baby, the Dog and the Angel. In today’s media-dominated world in which everyone is a Closet-Star, Keith Haring has managed brilliantly to picture a world with stark simplicity, sufficiently complex to allow every one of us a role.

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1982 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana

Untitled, 1983 | Chalk on paper | Photographer: Ivan Dalla Tana