I remember arriving in New York at the beginning of the seventies and, as I got to know the city better, being struck by a twofold image: on the one hand, the growth of new and glittering skyscrapers, and on the other, the apparently unstoppable invasion of its subway stations and cars and its streets by graffiti executed with multicolored spray paint.

I felt that a revolution was underway – a revolution which rejected the concept of total minimalism and functionality with its vision of modernity unrelated to humanity. The graffiti represented the need for a sign of humanity in a place where technology seemed to be getting the upper hand.

I remember Oliviero Toscani and I had decided to use the subway stations of New York for a series of photographs with Donna Jordan as the model, as for us the graffiti represented modernity better than the glass and steel facades of skyscrapers, however beautiful. I believe that the need for the post-modern had its origins in the same sensation that I had at the time, and that many others were to have.

Years later, recalling those emotions and at the suggestion of Tito Pastore (Fiorucci’s long-standing Art Director), we got in touch with Keith Haring, who had become famous after launching his career with graffiti in the subway stations of Manhattan, and who had become a friend of Andy Warhol, since he had been able to express the whole philosophy of that time and the spiritual needs of that moment with the skill of a great artist.

I will not go here into what has already been said in many books about Keith Haring. We were convinced that Keith was the right person to bring everything that he had achieved in New York to Milan in the shape of a great performance.

In 1984, we stripped bare our store, measuring 1,500 square meters, and asked Keith Haring to treat it as a space of his own, in which he would be able to create a great work of art. After talking it over with Andy Warhol, Keith had agreed to the initiative, partly because Andy told him that he had a great liking and esteem for Elio Fiorucci and for everything he had done and thought. Haring decided it would be very interesting to embark on this collaboration, as he, too, felt himself as being on the same spiritual wavelength. Keith also decided he wished to collaborate on the actual mural painting with his friend and protege Angel Ortiz (LA II), a wonderfully gifted sixteen-year-old graffiti writer.

In those years, this type of art was not a question of money, but of a common vision of the world.

The performance was broadcast on television and attended by a group of artists who arrived at the very beginning. It lasted two days and two nights, during which time the store remained open to all the inhabitants of Milan, who followed the performance with great curiosity.

The event has embedded itself in the memory of the Milanese as one of the most extraordinary, surprising, and modern of those years.

This essay is published in The Keith Haring Show

(Milan, Italy: Skira), 2005. P. 81 – 85.

Catalog edited by Gianni Mercurio, Demetrio Paparoni

Exhibition curated by Gianni Mercurio, Julia Gruen.

Fondazione Triennale di Milano

September 27, 2005 – January 29, 2006

William Burroughs

…but it wasn’t until 1983 that I actually met Keith…

Keith struck me as being rather spectral – as though he wasn’t there. He was strange yet very positive. I remembering seeing a very big show of his at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, and I was absolutely knocked off my feet by the large works in the show. Those paintings had a tremendous electric vitality. It was a very powerful experience for me.

In 1987, we had a big get-together of poets, writers, and painters in Kansas called The River City Reunion, which was organized by James Grauerholz. Keith came for that, and I remember him making a beautiful drawing on the sidewalk in front of the gallery where we had all gathered. He seemed shy and withdrawn – and yet he was very popular. He was never bothered by the crowds.

When Keith and I collaborated on Apocalypse, it was never a master-and-disciple kind of undertaking. Although Keith was young, he was not immature when it came to art. Our work was of equal weight and purpose. I found Keith’s art for Apocalypse completely astonishing. When I first saw his prints, it was a shock – but a good shock. My texts very perfectly understood and perfectly rendered. This was also the case when we collaborated on The Valley. For that, Keith made etchings, and they were exquisitely appropriate.

I think Keith is a prophet in his life, his person, and his work. In that way, he’s like Paul Klee, who was probably the most influential artist of the twentieth century – certainly through his art, his writings, his teaching. Keith will influence other painters – probably profoundly.

By association, Keith is part of the whole New York subway system. Just as no one can look at a sunflower without thinking of Van Gogh, so no one can be in the New York subway system without thinking of Keith Haring. And that’s the truth.

Leo Castelli

I held the show of Keith’s sculptures at my gallery on Greene Street, with enormous pleasure. The sculptures were quite marvelous, but the great surprise was when Keith said, “I want to paint a frieze all around the gallery.” The way he did it was fantastic – I should have filmed it. I mean, he painted these cartoon characters all along the walls, which measure over 100 feet, and he did this in one day! Incredible. I saw him at work, just inventing as he went along.

Someone once asked me, “If Keith Haring had appeared at your doorstep in 1960 or 1961, when Lichtenstein, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Warhol came to you, would you have accepted him into your gallery?” I answered that I would have found him entirely acceptable and interesting. In a way, I would have found him easier to take on than Roy Lichtenstein.

You see, Roy had taken things from the printed page – from the funnies – and made them his model. This is not the case with Keith, because he has a direct approach to what he’s doing. In the case of Lichtenstein, it was something really new – he appropriated something. But Keith is not at all an appropriator.

You can, of course, think of Keith Haring as somebody who is connected with comic strips – cartoons. But he made his own cartoons. Actually, I had a hesitation about taking on Lichtenstein. It lasted perhaps one or two days. Then I caught on to what he was up to. But in the case of Keith, there would have been no hesitation at all!

In thinking of Keith’s position in the art world… let’s recall the 1970s. It was a rather quiet period in the art world. It was quiet compared to the incredible flowering we had in the 1960s. But in the 1970s we asked ourselves, “Who will emerge now?” Well, what we got at the end of the seventies was German and Italian neo-expressionism. These new young artists came full force and we almost thought that our primacy was over. At the same time, we had people like Schnabel and Salle and Robert Longo – so America was tagging along too.

And then came Keith Haring. It was the early eighties and I certainly saw him as someone who was playing an important role. He came along with a group that included Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat and George Condo. Almost immediately, we had another group, the so-called Neo-Geo artists, and it was very interesting, because the group consisting of Haring, Scharf, and Condo didn’t really have time to develop. In a way, they were pushed to the side by this new movement. Anyway, the art-loving public wasn’t really in favor of the neo-expressionists. You see, we Americans are more influenced by a cartoon culture. That’s why Keith Haring is so important.

Henry Geldzahler

I met Keith while I was still the Commissioner of Cultural Affairs for the City of New York. I met him through Diego Cortez, who had organized a show called New York/New Wave at PS. 1, and a lot of underground artists were exhibited. This was 1981, and though I had already been aware of Keith’s subway drawings, I had not yet met him.

When I went to Keith’s studio, I saw genius. I saw someone in complete control. I saw someone with a signature style – a style he seemed to be born with. He seemed to me to be like Andy Warhol, someone who knew that what he was doing was important, and he didn’t care if he worked fourteen or sixteen hours a day. His work was his entire world because he knew that only his efforts from such and the recognition gained would really allow him to establish contact with the outside world.

The day I met Keith Haring at his studio, I went back to my office at Columbus Circle, and I invited the entire staff of sixty people into my office. I held up the works I had just purchased and said, “This artist is twenty-three years old. His name is Keith Haring and he’s a genius. If you can do it, go out and buy yourself one of his paintings. If not, just keep him in mind.” What I wanted to do, of course, was to make people aware of someone who would soon emerge as vitally important in the art world.

Timothy Leary

I see Keith Haring as the twenty-first-century archetypal artist. What I mean by that, is that the twenty-first century is going to be global – it’s going to break down all the national and geographic borders. And it’s going to be timeless, in the sense of the enormous spectrum of information that the world will be sharing. We’re also going to discover our youth in the twenty-first century. When I say it’s going to be global and timeless, I mean that it’s going to be sending out signals that will be recognized by anyone on the planet earth right now, and also for those who think back to the beginning of cave art when young Paleoliths were putting art on walls. And here’s Keith Haring being arrested by the New York City police for painting the wall! I must say that Keith may be controversial, but nobody really dislikes him. He may be shocking, subversive, offensive, but they all love him. They all know he’s the kid on the block who’s painting on walls.

And how mythic that he’s painting on walls for Afro-American young people! He’s addressing the real problem of New York City in the late eighties with this most powerful and tribal art! However, some people have asked whether Keith Haring is really a needed artist.

Well, in 1946, you had to have someone to express the psychology of the next forty years, and this happened to be a baby doctor. A pediatrician named Spock said, “Treat each child as an individual.” Keith is a child of Dr. Spock, and there are millions of Dr. Spock’s children with the notion of “express your individuality.” Keith is also a child of Marshall McLuhan, who said, “The medium is the message.” For Keith, his medium is his message. He’s there painting on walls and running around the world, and kids flock to watch him do it. Keith could jump into one of his wall paintings and we’d never miss him, because the spirit of the artist is just merging with the magic that’s suddenly appearing on the wall. It’s metaphysical! I mean, when you need someone like Dr. Spock, he comes along.

When you need an artist like Keith Haring, he comes along. I’m a linguist. I’m interested in language. I see everything in signs. And the messages coming from Keith… well, it’s difficult to separate Keith from his art – they’re really one. It’s hard to tease out the artist part of Keith. The way he looks. The way he moves. The intensity – the way he approaches a wall – with total openness, is the way he approaches you! He is, in the best sense of the word, childlike – open. Of course, like any young person he has tantrums, and he has low moments. He’s not Mother Teresa.

Some people have said that Keith Haring is a flash-in-the-pan. Well, it’s a good place to start. Because, first there’s the pan. Then there’s the flash. And the flash expands into an explosion and that gets space – velocity. What more do you want? People have criticized me. They said, “He was a brilliant professor at Harvard, but then he went off the deep end!” But what end should one go off? The shallow end? These metaphors! Of course Keith is a flash-in-the-pan. If you’re not a flash-in-the-pan you’re not going to get out of high school. You’re going to still be living back on the farm. I think Keith has made all the best enemies!

Keith and I …we’re mutants. We’ve been swept by the waves of the twentieth century into the twenty-first century. So we’re climbing on the shoreline. There are a few of us up there who are moving in the direction that our species will take in the next century. And there are poets and writers and painters, and millions of people who understand what we’re doing. But what are we doing?

Well, if you’re going to mutate and migrate into the future, you have to cut yourself loose from the schools, academies, institutions, and reputations of the past. Keith didn’t really go to art school. He didn’t get a Master of Fine Arts degree. He didn’t play those games. He suddenly popped out like a flower, like a seed in that cauldron of energy: New York City. And he put all his remarkable energy together – the wall, the easel, the canvas, the pigment… it’s a dance! No one has accused Keith of being serious. He’s so beautifully playful! All that energy shimmering and jumping!

Roy Lichtenstein

I once met Keith at the Milan, Italy, airport. He was in MiIan for his show at the Salvatore Ala Gallery. I stopped by the gallery a couple of days before the opening, and there was Keith creating his show right there, on the spot! I mean, the gallery had stretched all these canvases for him, and he was painting a show that would open in two days! It was extraordinary!

Keith composes in an amazing way. I mean, it’s as if he dashes the painting off – which in a way he does – but it takes enormous control, ability, talent, and skill to make works that become whole paintings. They’re not just arbitrary writings. He really has a terrific eye! And he doesn’t go back and correct – this is in itself amazing – and his compositions are of a very high level.

And he has such wit! His figures are just wonderful – the baby, the dog. I suppose Keith looked at our Pop Art – our cartoon figures – and realized they could be a part of art. Of course, he and I come out of very different backgrounds. I mean, Keith comes out of that whole graffiti school, while I was heavily into Abstract Expressionism. But then, I made a break, and Andy Warhol did too. Of course, the idea of doing cartoons is still something I feel isn’t completely accepted. Critical opinion still goes that way. I mean, it doesn’t seem intellectual enough, it doesn’t seem anguished enough. Criticism of Haring is very much the same.

Keith is a great showman. He likes being on the street and attracting attention – he attracts and likes the media. It’s a certain part of what he’s about. But he’s really not trying to make himself famous through advertising. He might like that, but it’s not the primary motive. It’s that he really wants people to love what he does. Also, Keith has a very interesting sense of humor. For example, those vases – those pseudo-Greek things, with Magic Marker on them. They’re quite convincing and charming and funny. And much of the stuff is quite sexy, yet it’s hardly pornographic. It’s quite happy sex!

What I like best about Haring’s work is that when he’s finished a piece, there’s nothing you could think of that you’d want to change. Even if he did something all at once without standing back and changing anything – there just isn’t a false move. It’s all so beautifully drawn – and there’s such a sense of relatedness. The stuff is beautiful! He’s really done some gorgeous things!

Madonna

Keith’s work started in the street, and the first people who were interested in his art were the people who were interested in me. That is, the black and Hispanic community – I’d say people from lower income and background. His art appealed to the same people who liked my music. We were two odd birds in the same environment, and we were drawn to the same world – and inspired by it.

I watched Keith come up from that street base, which is where I came up from, and he managed to take something from what I call Street Art, which was an underground counter culture, and raise it to a Pop culture for mass consumption. And I did that too. The point is, we have an awful lot in common.

Another thing we have in common – and this happened quite early – was the envy and hostility coming from a lot of people who wanted us to stay small. Because we both became very commercial and started making a lot of money, people eliminated us from the realm of being artists. They said, “OK, if you’re going to be a mass-consumption commodity and a lot of people are going to buy your work – or buy into what you are – then you’re no good.” I know people thought that about Keith, and they obviously felt that about me too.

So Keith and I are sort of two sides of the same coin. And we were very supportive of each other in those early days. I remember Keith coming to watch my first shows. That was down at the Fun House, where “Jellybean,” with whom I was involved, was the disc jockey. I’d sing and dance and I’d choreograph these scenarios – and we had taped music and it was great, because this was a Hispanic club-and the atmosphere was just charged!

I don’t know what drew us to these exotic clubs – like the Fun House or Paradise Garage. Obviously, it was the sexuality and the animal – like magnetism of those people getting up and dancing with such abandon! They were all so beautiful! I’ve always been drawn to Hispanic culture – and so has Keith. It’s another thing we have in common.

So these were the people who bought my records in the first place – and they’re a great audience to perform for. Keith keyed into that too. He’d give these great parties, and I’d go to them and I’d give parties and he’d come to them. And we had such fun!

Another thing we have in common… we have the same taste in men! I remember a funny story about people saying that I stole one of Keith’s friends. What happened was that I had a New Year’s Eve party, and Keith arrived with this incredibly gorgeous guy. I remember Keith saying, “He’s yours, Madonna. He’s your New Year’s Eve present!” I said, “Oh, thank you!” And there was this really stunning guy – a great dancer – completely happy and a great positive spirit. And so he became my friend, too.

Anyway, I’ve always responded to Keith’s art. From the very beginning, there was lot of innocence and a joy that was coupled with a brutal awareness of the world. But it was all presented in a childlike way. The fact is, there’s a lot of irony in Keith’s work, just as there’s a lot of ironyin my work. And that’s what attracts me to his stuff. I mean, you have these bold colors and those childlike figures and a lot of babies, but if you really look at those works closely, they’re really very powerful and really scary. And so often, his art deals with sexuality – and it’s a way to point up people’s sexual prejudices, their sexual phobias. In that way, Keith’s art is also very political.

What stays with me is that very early on, when Keith and I were just beginning to soar, our contemporaries and peers showed all this hostility. Well, the revenge was that, yes, there’s this small, elite group of artists who think we’re selling out. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is digging us! Of course, it’s what they want too! It’s so transparent! They’re just filled with jealousy and envy. And it certainly didn’t stop us, because Keith didn’t want to do his work just for the people of New York City – he wanted to do it for everybody, everywhere. I mean, an artist wants world recognition! He wants to make an impression on the world. He doesn’t just want a small, sophisticated, elitist group of people appreciating his work. The point of it all is that everybody is out there reaching for the stars, but only some of us get there!

When I think of Keith, I don’t feel alone. I don’t feel alone in my endeavors. I don’t feel alone in my celebration of what I’ve achieved. I don’t feel alone in the odds I’ve been up against. I feel so akin to Keith in so many ways! I really can’t compare myself to many people… and I don’t feel that many people can relate to where I’ve come from and to where I’ve landed. So when I think of Keith and his life and what he’s achieved… well, I feel that I’m not alone.

Yoko Ono

When Andy brought Keith to my son’s birthday party, Keith came in with this large canvas – still wet! Sean was nine years old that day, and Keith had incorporated the number nine with Sean’s face. I believe it’s one of the best pieces he ever did – it gives off such energy!

I have always thought Keith and Andy Warhol, who were such good friends and had so much in common, were really very different artists. Andy made statements that had a terrific sense of humor, but he treated his statements very, very seriously. I mean, when he painted the can of Campbell’s soup – that was a very humorous concept – but he treated the soup can in a very serious way. He had to do that to make his point.

With Keith, it’s exactly the opposite. Keith deals with very, very serious subjects, such as AIDS, but graphically. He, in turn, approaches such subjects in a very humorous, even uplifting way. So it’s the total reverse of Andy. That’s what makes Keith so interesting. I don’t think Andy would ever deal with material such as AIDS. He would deal with something very superficial – something that would reflect the superficialities of the world – and then treat it in a very serious way. So his direction was very different from Keith’s.

Keith has always stood outside the art world, because his art is the people’s art. In that way, he is like a record producer of pop music – of groups whose songs reach out to the people. John Lennon did that, and The Beatles did that back in the sixties.

Keith is doing exactly the same thing, and that’s why he communicates on such a big level. Keith is very accessible – and he’s also very kind, especially to children. He just has an innate ease of communicating with people, and most artists don’t have that ease. I don’t have it. But he does – and it’s amazing!

Brooke Shields

I wasn’t happy with the poster Avedon and Keith did of me. Frankly, I felt it wasn’t very respectful toward Keith – it was handled poorly, the point being that Keith’s art wasn’t properly understood. I thought it was unfair to Keith. But it was such fun working with Keith.

We had met some years earlier – in 1982, I think – and I was with a lot of people, including Andy Warhol. Andy kept taking a lot of Polaroids of me… and he made me feel as though I were a part of this whole underground culture. I didn’t know what to think… I was just seventeen.

At that point, my life was pretty hectic. I mean, I’d be at home sort of fighting with my half-sister one day, going to high school and doing a Vogue cover the next day, and going to the White House the day after! It was mad and hectic and wonderful. Well, soon after that, I went to Princeton University, where I graduated with a degree in French literature – I even received honors. That was in 1987. Anyway, before I went to college, Keith and I had dinner. He said, “I want to tell you something, and I hope you won’t be upset…” Well, he told me that when he first came to New York, he saw my Calvin Klein jeans billboard in Times Square, and he realized how fully I was a part of the culture of the time – of the eighties.

Then he sort of sheepishly said he had done these collages of me in Calvin Klein jeans which he combined with this nude man, and he made a kind of sexy double image. He said he hoped I wouldn’t be insulted at the thought of his having done this. Well, of course, I told him I didn’t mind. I completely understood his fascination with those ads. I mean, they did combine this incredible innocence with this unbelievable sexiness!

From the day Keith and I met, it was as though we’d always known each other. He wasn’t much of a talker – nor was I, but a lot was said without too many words being spoken. Keith is like an angel. His eyes are so innocent! He is that beautiful mixture of strength, which you can see in his work, and of childlike innocence, which you can see in his person. He’s very Through the Looking Glass!

Keith gave me a beautiful, beautiful drawing. It’s of a strange diaphanous creature blowing bubbles. On the back of it he wrote, “For Brooke, One of the sweetest (honestIy) people, with lots of love and respect. I learned a lot about humility, honesty, generosity and sincerity from you. Love you always… Keith.”

As I said, I wasn’t very verbal when I was young. Now, I’m twenty-four and I’ve learned to express my feelings more. Well, I recently met Keith again, and I said to him, “You know, I never said this before, but I really care for you. I just like being with you!” And he smiled and smiled!

This essay is published in The Keith Haring Show

(Milan, Italy: Skira), 2005. P. 81 – 85.

Catalog edited by Gianni Mercurio, Demetrio Paparoni

Exhibition curated by Gianni Mercurio, Julia Gruen.

Fondazione Triennale di Milano

September 27, 2005 – January 29, 2006

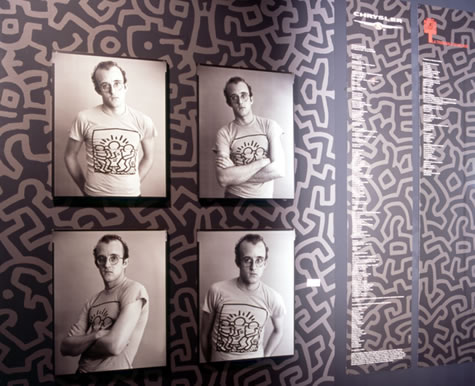

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano