The Pop Shop (1986-2005)

Nothing truly extraordinary can last forever. The sad reality is that everything good must someday come to an end. Some losses pass quickly, others are not soon forgotten. After nearly twenty years in business, Keith Haring’s Pop Shop closed last September. There was very little fanfare, yet many mourn the loss.

Not since learning that the artist was suffering from AIDS, or hearing word of his untimely death at thirty-one years of age, have such emotions been stirred. Haring had always been forthright, open and honest when he learned of his illness. He acknowledged it to the public-at-large in a Rolling Stone interview, yet there wasn’t much to soften the blow on that inevitable day in 1990 when he died.

For many, The Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in lower Manhattan’s SOHO district provided a sense of peace after Haring’s death. Established by the artist in 1986, The Pop Shop was open to everyone in a way that was impossible or impractical for a commercial gallery. While Haring’s artistic output was tragically cut short, his art (and something of his aura) could always be accessible through a visit to his Pop Shop.

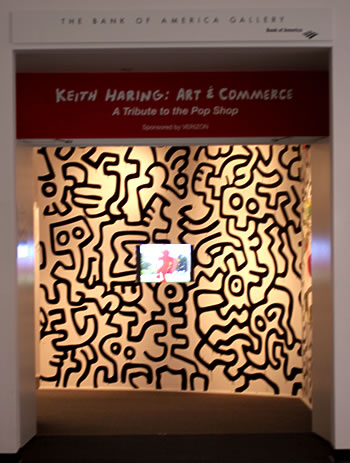

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Entrance

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

Admirers of Haring’s art made the pilgrimage, and never left empty-handed. Posters could be had for a dollar and “Radiant Baby” buttons for fifty cents. But, like the painted ghost on The Pop Shop’s mirror, one could feel the artist’s presence there long after his death.

Many of Keith Haring’s finest attributes in life seem to have been “embodied” in the store. All of The Pop Shop’s profits were distributed to children’s charities, educational organizations and AIDS-related causes in accordance with the mandate of the Keith Haring Foundation, established by the artist prior to his death.

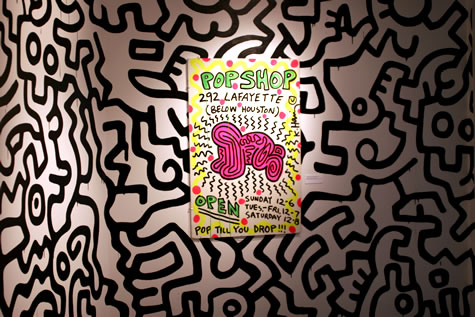

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

When The Pop Shop closed, there was such an enormous outcry from Haring fans and former patrons that the Foundation felt the need to allow postings at haring.com, resulting in an online forum. The response was overwhelming with many elegiac laments, personal recollections, and even a few complaints. Most, however, wrote simply to express a profound sense of loss. A feeling that what was once so accessible –and perhaps taken for granted — was now no longer available. Gone forever…like Keith.

The Formative Years:

When asked by a teenager why he had decided to become an artist, Keith Haring once responded that while growing up, drawing was his “only visible talent.” Haring was born on May 4, 1958, in Reading, Pennsylvania, and raised in nearby Kutztown. As early as he could remember, Haring had enjoyed drawing characters and illustrating stories. His father was an engineer whose hobby was cartooning. He taught his son (and later Keith Haring’s siblings) those basic skills and encouraged creativity. Aside from immediate family, Dr. Seuss and Walt Disney were Haring’s earliest influences. As he would later recall, “When I made the decision to be an artist, I began doing these completely abstract things.”1 He was emphatic that, “there was a separation between cartooning and being a quote-unquote artist.”2

By his early teens, Sunday school and independent Bible study had transformed the impressionable young Haring into a self-confessed “Jesus freak.” When his belief system and sense of belonging faltered, Haring turned to psychedelic drugs for both escape and artistic inspiration. He likened his drawings from this period to the Surrealists’ “automatic writing” and, like them, allowed the unconscious to guide his line. His discovery of the Rapidograph pen (a common tool for architects and illustrators at the time) permitted Haring to explore the continuous line. With the Rapidograph’s unique “capillary cartridge” combining the ink container and spiral in one, Haring was armed to hone both the fluid technique that would captivate spectators as he drew in public with chalk and the frame ‘n fill approach that would become his signature style.

The Steel City:

In 1976, after graduating from high school, Haring enrolled in the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh. Haring had been convinced by his parents and a guidance counselor to go to a commercial arts school. As he told Rolling Stone, “They said that if I was going to seriously pursue being an artist, I should have some commercial art background.”3 As Haring continued, “I quickly realized that I didn’t want to be an illustrator or a graphic designer.”4

Fortunately, the young artist, now well equipped with his Rapidograph and some commercial art training, was finding inspiration elsewhere. A timely Pierre Alechinsky retrospective at the Carnegie Museum of Art and the writings of both Jean Dubuffet and Robert Henri provided affirmation that Haring’s pharmaceutically-informed doodling might find broader acceptance with a fine art audience. So, after two semesters at the Ivy School, he dropped out.

The non-conformist Haring grew his hair long and explored the hippie-dom that he had been too young to participate in firsthand by hitchhiking across the country. He was a child in and of the ’60’s, weaned on television coverage of the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, the race riots, and the war in Vietnam.

Haring had yet to learn about Guy Debord and the Situationists5 or to collaborate formally on the funky haute-couture “Witches” Collection with Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, the puppet masters behind the Sex Pistols and British punk fashion, but he was already aptly applying Lettrist detournement (a technique of altering or subverting media images in order to put across a more radical or oppositionist message). Like Westwood and McLaren, Haring expressed his own irreverent “DIY” (“do it yourself”) notions about fashion as rebellion by transforming an appropriated image of President Richard Nixon sniffing a Drug Enforcement Administration (D.E.A.)-confiscated bundle of marijuana into an advertisement for “San Clemente Gold.” As Haring envisioned it, Richard Nixon’s “Western White House” became fertile ground for pot growing and the once humiliated ex-President had found gainful new employment providing a celebrity endorsement for top-quality product. The artist handprinted a dozen or more of his anti-Nixon/pro-legalization t-shirts to sell for food money and Grateful Dead concert tickets while on the road. In this, Haring’s first noteworthy venture into art and commerce, “San Clemente Gold” and the rock ‘n roll band logos he had mastered on blotter sheets (now silkscreened on tees) were providing modest (at best) financial sustenance for the artist’s beatnik-inspired travels.

In 1978, at nineteen, Haring had his first solo exhibition at the Clifford Gallery in the Arts & Crafts Center (now the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts). Aside from a major museum exhibition, this was the height of accomplishment for an artist in the Steel City. So, before the year’s end, Haring moved to New York, enrolled at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts (SVA) and became immersed in the burgeoning East Village club, art and social scene.

SVA & NYC:

In July 1978, Warner Brothers released the debut album of Akron, Ohio’s Dada-literate robot rock quintet Devo. David Bowie (for whom Haring would later design cover art) had dubbed them “the band of the future” and their seminal “Q.: Are We Not Men? A.: We Are Devo!” record would indeed lay the groundwork for the explosion of synthesized Pop and so-called New Wave music to follow. With “Mongoloid,” “Jocko Homo,” and “Uncontrollable Urge” blasting from a cassette in Haring’s boom-box, this album became a rallying call and a conduit for the like-minded to meet. As artist Kenny Scharf recalls: “It was September of 1978 and I was on my way out to the lobby [of SVA] when the rhythmic new wave beat of Devo lured me into a side room. There before my eyes I saw Keith, rapidly painting himself into the corner of the room which he had transformed into an all-over (floor, ceiling, walls) Dubuffet-like environment with strokes done to the beat of the music, almost like a dance. At that moment I knew I had found a fellow freak…We became immediate friends.”6 This early performance foreshadowed the very public subway chalk drawings that would soon make him famous, and the resulting “all-over” SVA installation was a necessary antecedent to the walls, floor and ceiling of his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street. (Later to avoid arrests by New York City Transit cops, the subway became his means of escape, and in painting the Pop Shop interior, the now more experienced artist had already learned to work his way toward the door.)

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Installation View (Brooke)

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

At SVA, Haring studied semiotics – the language of signs and symbols. He was looking for an appropriate means to communicate his message with the effectiveness of advertising. In 1980, Haring noticed unused advertising spaces covered with matte black paper in a subway station, and began to create white chalk drawings on the blank paper panels. The artist made hundreds of “subway drawings” over the next five years (as many as forty on a single day), and New York City commuters responded. Haring would use the subway to experiment with ideas. It was his urban and underground equivalent to the public and participatory art of Christo’s “Running Fence,” and Haring used this forum to develop his iconic characters: flying saucers, barking dogs and his personal “tag,” the radiant baby.

In 1981, Keith Haring made numerous day-glo and felt-tip tracings of Brooke Shields taken from seductive Calvin Klein advertisements to critique the company’s use of a then-15-year-old actress/model in pitching designer jeans by declaring, “Nothing gets between me and my Calvins.” The year prior, Haring had altered countless Chardon/Paris jeans ads in situ (depicting a woman embracing a man at waist-level) by blotting out the letter ‘c’ and the accent over the ‘o’, so they read ‘hardon’. According to Barry Blinderman in his essay, “Close Encounters with The Third Mind”: “This act foreshadowed the artist’s decade-long desire to co-opt the ad world’s insidious subliminal encoding strategy–whether by handing out ‘radiant baby’ buttons by the thousands, infiltrating the subway advertisements’ domain with his chalk-on-black paper drawings, or mass-producing refrigerator magnets. In all these cases he was providing alternative ads, promoting consciousness-raising rather than consumerism–or ‘Crack is Wack’ rather than ‘Coke Is It.'”7

Installation View, 2006

Art and Commerce (North Wall)

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

Being a Kind of Mirror:

Haring saw scarce difference between Madison Avenue marketing and the gallery system that had begun to sell his paintings. His mentor (and later his dear friend), the Pop Art icon, Andy Warhol had boldly declared, “Business art is the step that comes after Art.”8 According to Warhol, “Making money is art,” and “good business is the best art.”9 Once Haring’s paintings had begun to sell, he was accused of “selling out.” Yet, as the artist later wrote, “It’s about understanding not only the works, but the world we live in and the times we live in and being a kind of mirror.”10

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce (case)

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

According to Haring, “Andy set the precedent for the possibility for my art to exist.”11 Additionally, he continued, “Andy practically ‘convinced’ me to open the Pop Shop when I started to get ‘cold feet’.”12 Haring’s critics were given a unique opportunity to level attacks about crass commercialism when he opened his store to the public on April 19, 1986.

Words like “Capitalist” and others too rude to mention:

As Haring wrote in his journal, “Very few people understand why someone would want to open a shop and not make money.”13 In describing that rainy Saturday afternoon ribbon-cutting ceremony, Michael Gross of The New York Times missed the point by writing: “Mr. Haring used to offer his art free on subway walls. Now he sells it for five-figure sums. Mr. Haring also used to give away his pins, jigsaw puzzles and comic books, which are now for sale at the shop.”14 According to the Times, “That may be why someone spray-painted its threshold with words like ‘Capitalist’ and others too rude to mention.”15 Yet, making money was never Haring’s intent.

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce (Coat)

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

In his journals, Haring stated that the reason he felt at liberty to create paintings for the gallery, make a Grace Jones video for MTV, create vodka ads, and open his Pop Shop without fear of compromise or contradiction was that all these opportunities had arisen naturally. Haring believed it was simply a question of being honest with yourself and your times. It was less about “purity” and much more an issue of integrity. He wrote in his journal, “There isn’t much difference between the people I have to deal with in the art market or in the commercial world.”16 The artist continued, “Once the artwork becomes a ‘product’ or a ‘commodity’ the compromising position is basically the same.”17 As the artist reveals in John Gruen’s Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography: “Of course, the Pop Shop was an easy target, and it was attacked from all sides. People could now say, ‘What do you mean Haring isn’t commercial? He’s opened a store!’ But I didn’t care…it’s an art experiment that works.”18

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

With the opening of The Pop Shop, Haring had reason to cease drawing in the subways. “These drawings had run their course, because they had achieved what I wanted them to achieve and that was getting the work out to the public at large.”19 The artist continued, “I also stopped because the subway drawings were disappearing. Word had gotten out that my prices were rising more and more and people just cut the drawings out of their panels and sold them.”20 In fact, according to one account, a “street artist,” disgruntled with Haring’s rapid rise to fame and apparent fortune, purchased large sheets of archival paper from New York Central Art Supply to mimic the material glued over old advertisements by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). This artist acquaintance now admits to strategically peppering the subway billboards along Haring’s regular path with these deceptive black paper panels cut to fit and installed with double-sided tape (versus the wheat-paste favored by the New York City Transit). Thus, Haring’s fresh chalk drawings could be easily removed and collected just minutes after the unsuspecting artist had departed the scene.

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Pop Shop Poster, 1986

Ink on Paper | 22 by 30 inches | 56 x 76 cm

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

Contrary to The New York Times report, except when “liberated” by an act of vandalism (equal to or greater than the artist’s own), Haring’s subway drawings were never “free.” They were never signed, never given monetary value by the artist, nor intended for the art market. Haring thought of these drawings as time-based ephemera. Performance relics? Perhaps, while they lasted. But, most importantly, the subway drawings were a grassroots campaign to reach people–as many and as diverse a group as possible.

Communication, Not Commerce:

According to Haring: “I wanted to continue the same sort of communication as with the subway drawings. I wanted to attract the same wide range of people, and I wanted it (The Pop Shop) to be a place where, yes, not only collectors could come, but also kids from the Bronx.”21 The Pop Shop’s philosophy was simple. Haring continued: “The main point was that we didn’t want to produce things that would cheapen the art…This was still an art statement. I mean, we could have put my designs on ‘anything’…We sold the inflatable baby and the toy radio and, mostly, a wide variety of t-shirts, because they’re like a wearable print–they’re art objects.”22

Installation View, 2006, Art and Commerce

Skateboards, 1986 | Marker on Skateboards

Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida

Photographer: Andrea O’Brien

Two years after Haring opened his Pop Shop, Marcia Tucker wrote in her Preface to the New Museum of Contemporary Art’s catalogue, Impresario: Malcolm McLaren and the British New Wave: “According to certain postmodernist theories, the traditional modernist avant-garde no longer exists, having exhausted itself or, in its turn, having been co-opted by the forms of popular culture. Some have even called this process a democratization of culture whereby popular forms replace those of the bourgeois avant-garde. Or perhaps it is more a matter of displacement–that slippery moment when art becomes commerce, shifting back again into the cultural arena as another kind of commodity. The catch is, even today, in 1988, few among us are willing to acknowledge that certain mass cultural forms and practices may comprise the most significant ‘culture’ of our time, precisely because of their ‘popular’ character.”23

A Combination of Inc. and Ink

In describing a satellite venture in Japan, Haring wrote: “Pop Shop will go up in a temporary building on a temporary location for a temporary time…The whole concept is perfectly in keeping with my aesthetic.”24 Like his short-lived Pop Shop in Tokyo and the ephemeral subway drawings, Haring must have realized his New York store would last only so long. Now that The Pop Shop is gone, “Keith Haring: Art & Commerce” pays tribute. Like the artist who created it, The Pop Shop was always infinitely more about art than commerce. Yet, Keith Haring understood his role in helping to merge the two. In his October 7, 1987, journal entry, the artist wrote: “I just boarded the plane to Nice. It’s funny to me how many different ways my name gets spelled on boarding passes, but this is the best. I’ve seen Harding, Harving, etc., but this one says Harinck. [It] looks/sounds like a combination of Inc. and ink; I like that.”25

Footnotes

- Keith Haring in David Sheff, “Keith Haring, An Intimate Conversation,” Rolling Stone, no. 558 (August 10, 1989), pp. 58-66.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Situationists were a libertarian group of avant-garde artists and intellectuals influenced by Dada, Surrealism, and Lettrism who came to prominence during the May-June student rebellion in France in 1968.

- Kenny Scharf, “Keith Haring,” Keith Haring: The SVA Years (1978-1980) (New York: SVA School of Visual Arts, 2000), p. 13.

- Barry Blinderman, “Close Encounters with The Third Mind,” Keith Haring: Future Primeval (Normal, Illinois: University Galleries, Illinois State University, 1990), pp. 16-17.

- Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), p. 92.

- Ibid.

- Keith Haring, Keith Haring Journals (New York: Viking, 1996), p. 119.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- Ibid., p. 118.

- Ibid., p. 116.

- Michael Gross, “Notes on Fashion,” The New York Times (April 22, 1986), p. A22.

- Ibid.

- Haring, p. 209.

- Ibid.

- Keith Haring in John Gruen, Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography (New York: Prentice Hall, 1991) p. 148.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Marcia Tucker, Impresario: Malcolm McLaren and the British New Wave (New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988), pp. 7-8.

- Haring, p. 138.

- Ibid, p. 182.