This interview was made by Sylvie Couderc, with the collaboration of Syivie Marchand.

Transcription Sylvie Marchand.

Those ten paintings are entitled ‘The Ten Commandments”. Could you comment on this title, and on how you referred yourself to the Bible? Did you reread the book?

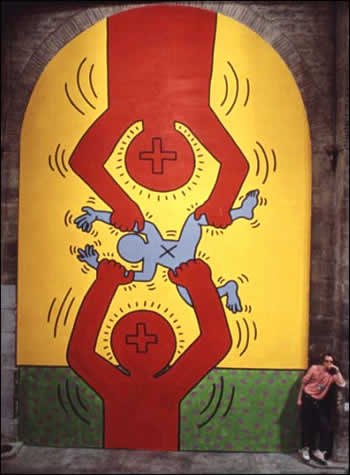

I could not remember what the “Ten Commandments” were so I had to get a bible when I got here. I read them and took a few notes to think of it before I started working. For me they rapidly became metaphors. For some of the ideas are a little abstract, so the picture that represents them can be about other things at the same time, like “honor the Sabbath” for instance. The way I worked on the “Ten Commandments” is: even though its says “thou shalt not steal”, the picture I show is someone stealing: the antithesis. I present what not to do instead of saying “this is what you should do”. And at the same time there are things that allude to other ideas. If you did not know that they are the “Ten Commandments”, you would probably read a different story.

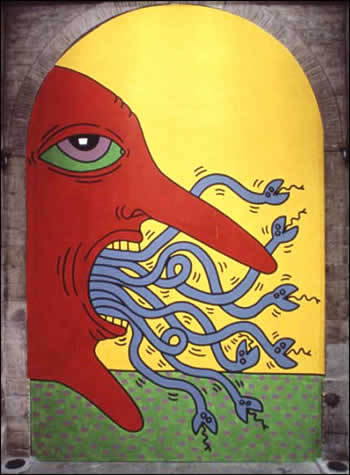

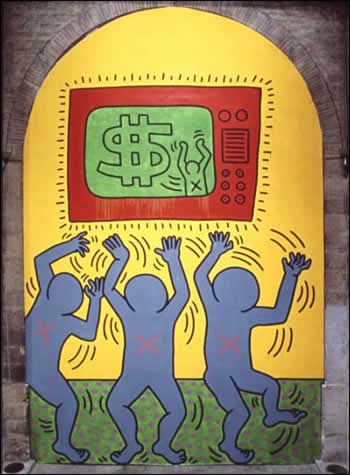

The Ten Commandments 1, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

You have chosen to display a drawing by Matisse at the entrance of the exhibit, as an introduction to it. Why so?

Jean-Louis Froment asked me what work I would choose if I had to pick one as an interaction with my show. I picked Matisse for the simplicity of his line, and because he’s been one of my favorite painters for a long time. But also because those particular drawings were done for a chapel and the arches here remind me very much of a church. There is some kind of religious connotation to it. Matisse’s drawing is about taking Christ to the cross, and in a way he was doing a more literal translation of the story of the Bible, not trying to add other metaphors. His work is more about drawing than about information.

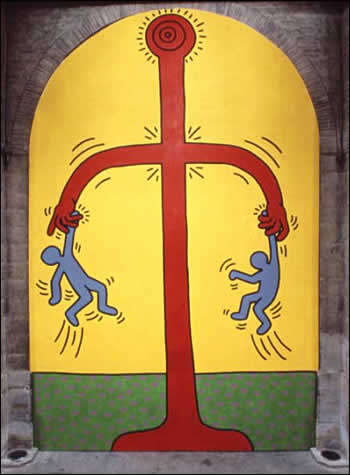

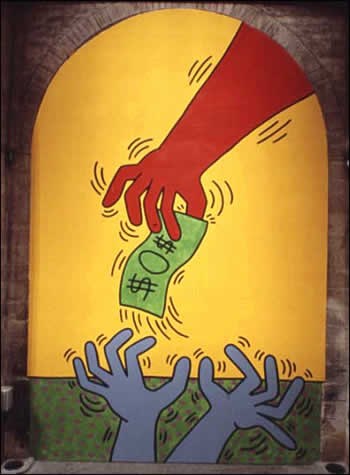

The Ten Commandments 2, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Don’t some of your works take their cue from ancient paintings, especially those of pre-Columbian civilizations? How important are primitive arts for you?

For me it was very interesting how obviously early abstract painters like Braque, Picasso, or Brancusi really were directly inspired by things that were starting to turn up for the first time from Africa. You can see pictures of African sculptures in their studios; and in their paintings you notice that they put all of that directly through their western idea of art. With me it’s not so much looking at or trying to imitate as much as it is trying to embody the idea of “primitivism” in my own approach to the work and my attitude towards drawing and towards the world.

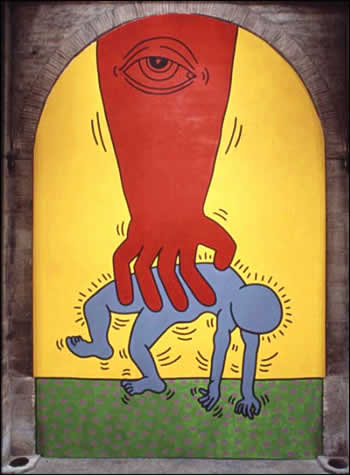

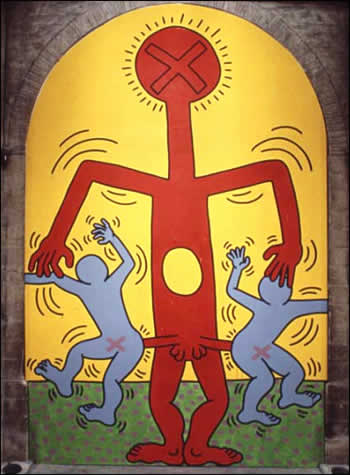

The Ten Commandments 3, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

This attitude provides the basis on which you develop a mythology and a bestiary that are very personal to you.

The vocabulary of my images became “physical”, almost; it’s a vocabulary of signs and symbols evoking different ideas, and gaining meaning through repetition and juxtaposition, changing meaning as they appear over and over, as I use them in different situations. Images gain power with repetition. There are some images that I will only use once, and not use again because they don’t seem to really hit the nail right on the head, but there are some which are so strong they have to be reduced; sometimes just reusing them makes them stronger.

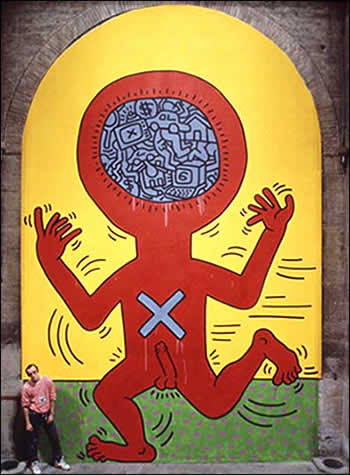

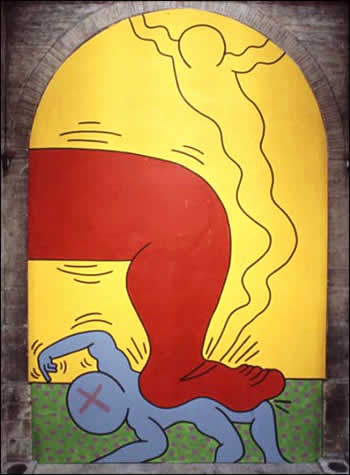

The Ten Commandments 4, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Where do those images arise from?

There are things that Jung said about the collective unconscious. I don’t know if I can talk about “dream work” because I don’t really get things specifically from my dreams… It’s more an awareness of universal images which I “digest” and put in my own series of explanations and definitions. I reorder things with my own imagination. I try as much as possible to let the drawings happen by themselves. I become a vessel for this information, for this kind of magic, the spirit that flows through me and creates this thing.

The Ten Commandments 5, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Taking a close look at your drawings and paintings, one notices that you paint them with great freedom, integrating the drippings and the spots into them. Is this another means of preserving this spontaneity you just mentioned?

The dripping… well, if it happens, it happens; it does not take anything from the work. The dripping just proves that you were not trying to control the work, but the work was developing by itself and if it drips, it’s a natural part in the evolution of the work. I think you have to control the materials to an extent, but it’s important to let the materials have a kind of power for themselves; like the natural power of gravity, if you are painting on a wall, it makes the paint trickle and it drips; there is no reason to fight that. It becomes part of the experience, part of the act of doing it, also because a lot of the things are records of a particular moment: to go back and change it later would be changing that moment and manipulating something that was very immediate and fresh.

The Ten Commandments 6, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Haven’t your paintings become more colorful lately?

I have been using color since I was a kid; but for a while there was a misconception that I did not use color because what I did in the subway was basically chalk on black paper. But when I started painting on canvas, then I could use the full range of colors again. in the “Ten Commandments”, from one panel to another, I began to make connections with the red always being the color representing power. If I were asked to use three colors it would be black, white and red, for they are the three strongest colors, and yellow would be my next choice. Red is one of the strongest colors, it’s blood, it has a power with the eye. That’s why traffic lights are red I guess, and stop signs as well… In fact I use red in all of my paintings.

The Ten Commandments 7, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Would you say that the color red has negative connotations?

Yes, to the extent that it has always been associated with the devil, fire, hell, and stop signs!

Violence, sex and money are prevailing motives in your work. Does this mean that you are critical of America today?

I grew up in the sixties, watching people trying to oppose the war in Vietnam which was obviously wrong to me as a child. It seemed ridiculous to be fighting when you did not even know what you were fighting about… and growing up watching race riots on TV, J.F. Kennedy being shot, Jimmy Hendrix dying, seeing people being assassinated just for what they believed in… all these things had a strong impression on me as I was growing up. All these political ideas are stuck with me. Although the generation. that is growing up after me seems to be growing up in a cloud of apathy.

The Ten Commandments 8, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Could you expand on just what your interest in media culture is?

Being American, media are my main source of information. There is an illusion in America that what is produced there is sent anywhere else in the world and it is partly true; but I don’t think Americans realize enough that they are not the center of the world. But for me, it’s my main source of information since I live there.

The Ten Commandments 9, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

In your opinion, does the artist have to play a specific role in today’s society?

I think as much as possible, an artist, if he has any kind of social or political concern, has to try to cut through those things, and to expose as much as possible what he sees so that some people think about things that they don’t normally think about. Sometimes I do that by pushing things to the extreme; in the face of people who try to close their eyes I react the opposite, by trying to be more open and deal more openly with sexuality and violence for instance. An artist putting as many images into the world as I am should be aware or try to understand what that means and how those images are absorbed or how they affect the world. I don’t think art is propaganda; it should be something that liberates the soul, provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further. It celebrates humanity instead of manipulating it.

The Ten Commandments 10, 1985

Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Bordeaux, December 16,1985.

This interview was made by Sylvie Couderc, with the collaboration of Syivie Marchand.

Transcription Sylvie Marchand.