For a generation of 80s art lovers, Keith Haring’s work summed up New York cool. Andy Warhol, Elton John and David Bowie were collectors of his paintings; Madonna, Grace Jones, Dennis Hopper and William Burroughs were among his many friends. By the start of the decade, he’d forged an entirely fresh aesthetic, with roots in punk, hip-hop and the late 70s craze for street graffiti, which thrived in the subways of the Lower East Side, The Bronx and upper Manhattan. During his short career, his jellybean-like doodles in unapologetically garish colors would become familiar on posters, T-shirts, even mugs and key-rings. Such apparently throwaway work has sometimes blinded people to its political content.

The Guardian, Title Page, 2001

In 1982, for example, he painted an anti-nuclear poster, then gave away 20,000 copies that he’d paid for himself at a demonstration in New York’s Central Park. Likewise, his Free South Africa posters were distributed at an anti-apartheid demo three years later. He was fiercely anti-Republican – a portrait of Ronald Reagan had the president holding up a torch marked with the devil’s number, 666. And, at the height of his fame in 1989, Haring attacked the prejudice surrounding the growing Aids crisis with his painting Silence = Death, which features figures covering their eyes and ears and a pink triangle (the badge gay men were forced to wear in the Nazi death camps, and appropriated in the 70s and 80s as a symbol of gay pride).

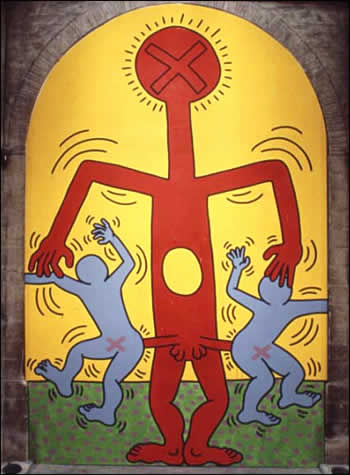

Another bugbear was organized religion. Take Haring’s 1985 series of paintings, The Ten Commandments, about to go on show at Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, London. The giant canvases, commissioned to fit the 10 arches of an entire floor of the Bordeaux Museum of Art, don’t illustrate each commandment, but jumble them up. Yet there is a logic there, too: oppressors and oppressed are color coded, blue figures denoting the exploited, red figures the tyrannical – and probably referring, also, to Hell. The most sacrilegious image shows a God-like giant with two penises assaulting two of his “flock”.

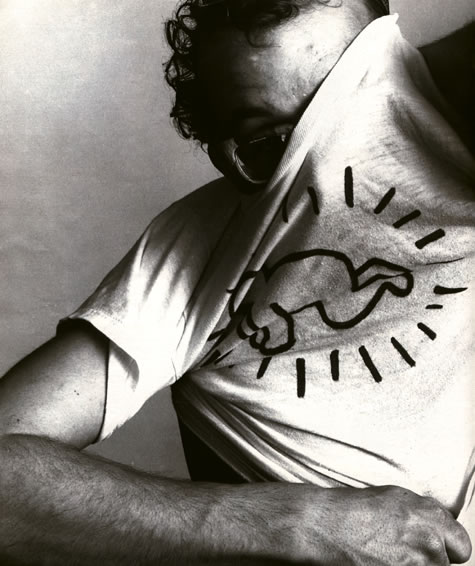

The Guardian, 2001 Keith Haring, Photographer: Robin Holland

Haring claimed he came up with the idea while he was out clubbing. “It’s so obvious,” he recalled later. “Since it’s 10 arches to be painted, why not the Ten Commandments? While I’m dancing, I try to think of as many commandments as I can, but can only think of a few. So the minute I get to Bordeaux, I ask for the Bible.” And, typically, he left the execution to the last moment. Once he had arrived at the museum, he had three days to complete the 19ft by 25ft canvases; he worked around the clock to meet his deadline propelled along, in the final hours, by amphetamines. The show was a hit, the opening party a blast, attended by, among others, Helmut Newton, who photographed Haring in a gold lame tuxedo for Vanity Fair.

Free South Africa, 1985, Poster

Haring adored being the centre of attention and partied as hard as he painted. To New York’s groovy underground culture, he was the pip in the Big Apple. Socially, his biggest asset was Warhol, whom he had met at an exhibition in 1983. The two enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, Haring feeding Warhol the latest youth culture, Warhol easing Haring into star-studded circles. Haring hobnobbed, too, with the great disco divas and drag queens of the day: Gwen Guthrie, Jocelyn Brown and Lady Bunny. His spectacularly theatrical parties became legendary. At one of his birthday bashes, Boy George sang Happy Birthday. At another, Madonna trilled Like A Virgin on a bed strewn with white roses.

It was far away from Haring’s Middle America roots. He was born in 1958, in Reading, Pennsylvania, to strait-laced, Republican parents, and as a child developed a passion for Disney and Dr Seuss, and spent his time drawing cartoons with his father. In the mid70s, while reluctantly studying commercial art at Pittsburgh – at the behest of his parents, who considered it a more prudent option than fine art – Haring was a hippy with a long, unbecoming plait, who frittered away his leisure time listening to the Grateful Dead and smoking dope. Flunking out of college, he took on a series of bum jobs and by the time he reached tolerant, gay-friendly New York in 1979, he was gagging to make up for lost time. “New York was the only place I would find the intensity I needed and wanted for my art and life,” he said. “Haring was a white boy from small town America, who responded to and drew energy from the culture and music of New York’s black and Latino population,” recalls Julia Gruen, Haring’s assistant from 1984 to 1990. “He started out living the cheap, student life in Lower East – room-mates, mundane jobs, intoxicating night life, promiscuity….”

Ignorance = Fear, 1989, Poster, 24 x 43 1/4 inches

He was drawn into the arty punk scene, typified by the club CBGB’s, where Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Blondie and the Ramones played. By day, he studied at the School of Visual Arts or practiced his early street art, slapping collages of New York Post headlines bearing subversive messages such as “Reagan slain by hero cop” on to news-stands or lamp-posts.

Like Warhol, Haring was initially cold-shouldered by the American art establishment. (His work was far more popular in Europe.) “Haring disappointed the American art world by sidestepping the common means of entry into that rarefied sector, by bringing art to the people without the guidance of an art world savant,” explains Gruen.

By night, he visited the gay bathhouses, notorious S&M sex club the Anvil, and East Village dives such as Club 57, the Mudd Club and Paradise Garage. His relationships were not as successful as his social life. “It’s one of my major faults that I pursue physical love with such obsession,” Haring said. “I always felt intellectual stimulation could be provided by others. From the beginning, this pattern was a source of trouble and frustration.” He worried about his weedy, nerdy, bug-eyed appearance – not helped by his clunky glasses and barely mitigated by his hip-hop-lite attire of high-top Nike trainers and baseball cap worn back to front – and tended to fall for stunningly good-looking Latinos.

The emerging overlap between punk and hip-hop, of which Haring was so much a part, became explicit in 1981, when The Times Square Show, a mammoth art exhibition organized by avant-garde art collective COLAB, brought writers and post-punk artists together, just as graffiti art began to appear in alternative art spaces. A good example is the video for Blondie’s 1981 hit Rapture, where Debbie Harry struts around a yard, rapping about New York graffiti artists such as Fab Five Freddie, while others spray paint the walls. Haring’s graphics, meanwhile, decorated the cover of Scratchin’ – A Six Track Hiphop Party Mix, the 1984 album by ex-punk Malcolm McLaren and The World’s Famous Supreme Team Show.

By the early 80s, Haring’s drawings and paintings were full of twitching, cartoon figures, dogs and TV sets, whizzing flying saucers and throbbing phalluses in Day-Glo colors – the favoured palette of punk and new-wave graphics. And, in 1982, soon after his first encounter with break-dancing, some of his characters started to spin and twist on their heads.

Using a fat, squeaky Magic Marker, Haring also drew his figures on New York’s streets. A central image in his work is the “radiant baby”, recalling his love of comic strips with its cartoony motion marks. To anyone who spotted him perform his next seditious trick (tagging – scrawling over – the panels of black paper pasted over out-of-date ads in the subways), Haring handed out button badges splashed with his radiant baby – a continuation of that very punk fashion for tiny badges bearing the names of bands.

The Ten Commandments, 1985 Acrylic, oil on canvas, 17.5 x 25 feet

Haring was always a populist. This is borne out by his graffiti, accessible pop imagery, his many community projects undertaken for free and his Pop Shop boutique, on New York’s Lafayette Street. Set up in 1986, in a democratic bid to bring his art within the reach of “not only collectors but kids from The Bronx”, the latter sold – and still does sell – T-shirts, badges and all manner of knick-knacks emblazoned with his unmistakable imagery. This, together with his gargantuan output – he was working right up to his Aids-related death, aged 31, in 1990 – led to an over-exposure that has caused some to write off his work as at best mere graphics, at worst tacky doodles.

His admirers stayed loyal; William Burroughs said of a show at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, “I was knocked off my feet by the large works on show. They had tremendous electric vitality. It was a very powerful experience for me.”

Judging by the current vogue for early 80s street chic, Keith Haring’s image is ripe for a reappraisal. Graffitied togs are a hot fashion story this summer. Musically, the 80s electro sound is back, London’s Scala holds monthly hip-hop nights, and S Club 7’s recent Top Of The Pops appearance featured – albeit lamely – break-dancing.

“Keith’s death led some to condemn, some to canonise,” says Gruen. “But the work survives – and through it his spirit”.